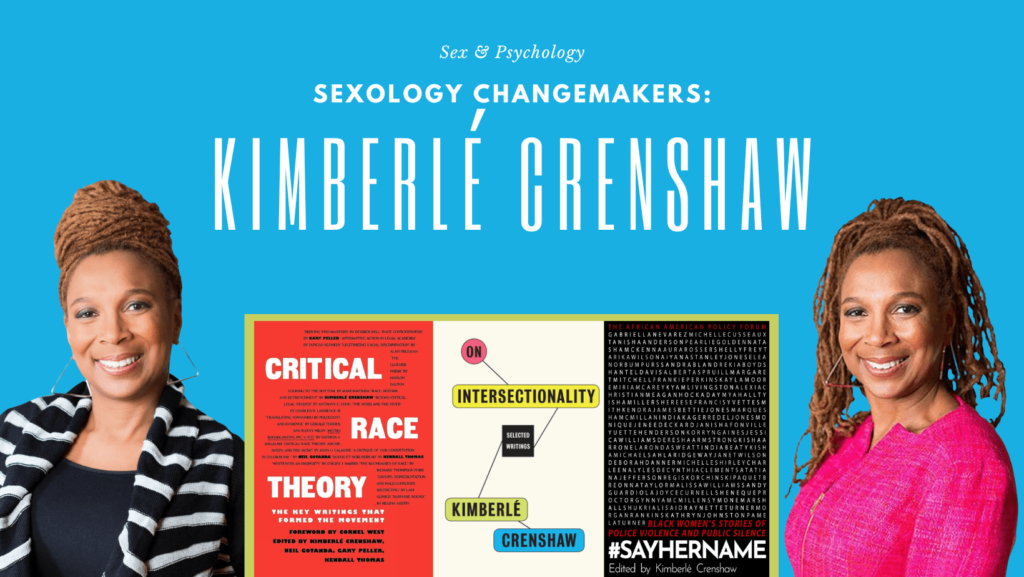

Kimberlé Crenshaw is an African American civil rights activist and one of the foremost scholars on critical race theory and Black feminist legal theory. Her work on intersectionality has had a huge impact on how we understand the layers of oppression that individuals face based on their social identities, which is why we have chosen to highlight her as part of our sexology changemakers series.

You can also read about Shere Hite, Virginia Johnson, and June Dobbs Butts, who are some of other key “hidden figures” in sexology previously highlighted in this series.

Education and Career

Crenshaw has spent over 30 years as an activist and scholar to “identify key issues in the perpetuation of inequality,” particularly in relationship to how the law reflects and sustains these inequalities between groups. She first received a B.A. from Cornell University, which she followed with a J.D. from Harvard Law School and an L.L.M. from the University of Wisconsin.

In 1991, Crenshaw was part of the legal team for Anita Hill during her case against Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas. This experience illuminated the way that treating race and gender as separate identity categories erases the distinct experience of Black women, demonstrating the importance of an intersectional approach to social identity.

Currently, Crenshaw is a Professor of Law at Columbia University, a Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of California, Los Angeles, the Co-Founder and Executive Director of The African American Policy Forum, and is the host of the Intersectionality Matters! podcast.

Intersectionality

Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” in a 1989 article in the University of Chicago Legal Forum titled “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” [1]. In this article, Crenshaw uses three different case studies of legal proceedings to demonstrate how the court’s treatment of racial and sexual identities as separate domains of discrimination ignore the multidimensional experience of Black women, who experience an interlocking axis of oppression due to their unique subject position. Crenshaw explains:

With Black women as the starting point, it becomes more apparent how dominant conceptions of discrimination condition us to think about subordination as disadvantage occurring along a single categorical axis. I want to suggest further that this single-axis framework erases Black women in the conceptualization, identification and remediation of race and sex discrimination by limiting inquiry to the experiences of otherwise-privileged members of the group. In other words, in race discrimination cases, discrimination tends to be viewed in terms of sex- or class-privileged Blacks; in sex discrimination cases, the focus is on race- and class-privileged women. (p. 140).

In this article, Crenshaw provides an example of crucial importance to sex researchers that demonstrates the necessity of intersectionality; the obscuring of Black women’s experiences during feminist discourses on rape. She explains how rape was conceptualized as a tool of male domination over white femininity, a discourse which “tends to eclipse the use of rape as a weapon of racial terror” (p. 158). To this end, Crenshaw continues:

When Black women were raped by white males, they were being raped not as women generally, but as Black women specifically: Their femaleness made them sexually vulnerable to racist domination, while their Blackness effectively denied them any protection. This white male power was reinforced by a judicial system in which the successful conviction of a white man for raping a Black woman was virtually unthinkable. (p. 158-159).

This excerpt makes clear the importance of applying intersectionality in sex research, particularly among scholars who study sexual and/or gender based violence, as well as those who study the legal ramifications of sexual activities.

Intersectionality is further developed by Crenshaw in an article titled “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color,” published in the Standford Law Review in 1991. [2] Here, she applies intersectionality more broadly to “the various ways in which race and gender intersect in shaping structural, political, and representational aspects of violence against women of color” (p. 1244).

Impact on Sex Research

The impact of intersectionality on how sexologists have conceptualized sex research is profound. Before Crenshaw introduced the concept, identity categories such as race, sex, and gender were all treated separately. However, as Crenshaw explains, separating these categories ignores the specific experiences of individuals who hold intersecting identities. For example, the experiences of Black lesbian women are inherently different from white lesbian women, despite the fact that the two groups share the identities of “lesbian” and “women.” Intersectionality, then, allows sex researchers to be more accurate when studying individuals from marginalized groups as not to ignore crucially important aspects of their identities.

Although it is difficult to quantify the impact that Crenshaw has had on the field of sex research, searching “intersectionality” among articles published in the Journal of Sex Research, for example, yields over 260 results. Some of the research published using her intersectionality framework include:

- Intersectional Experienced Stigma and Psychosocial Syndemic Conditions in a Sample of Black Men Who Have Sex with Men Engaged in Sex Work (BMSM-SW) from Six US Cities

- An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of Black Women’s Meaning and Experiences of Sexual Anxiety

- “This Is To Help Me Move Forward”: The Role of PrEp in Harnessing Sex Positivity and Empowerment Among Black Sexual Minority Men in the Southern United States

It is clear that Crenshaw’s work is crucially important not just the fields of critical race theory and Black feminist legal studies, but also sex research. However, there is still plenty of room sex research to grow when it comes to studying intersections of oppression and marginalization. You can follow Crenshaw and keep up with her work on Instagram, Twitter, and the AAPF website.

Want to learn more about Sex and Psychology? Click here for more from the blog or here to listen to the podcast. Follow Sex and Psychology on Facebook, Twitter (@JustinLehmiller), or Reddit to receive updates. You can also follow Dr. Lehmiller on YouTube and Instagram.

Image Credit: Collage made with Canva,

Images sourced from Columbia Law School and UCLA Newsroom

References

[1] Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139–167. [2] Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039The post Sexology Changemakers: Kimberlé Crenshaw appeared first on Sex and Psychology.

[ad_2]

Article link